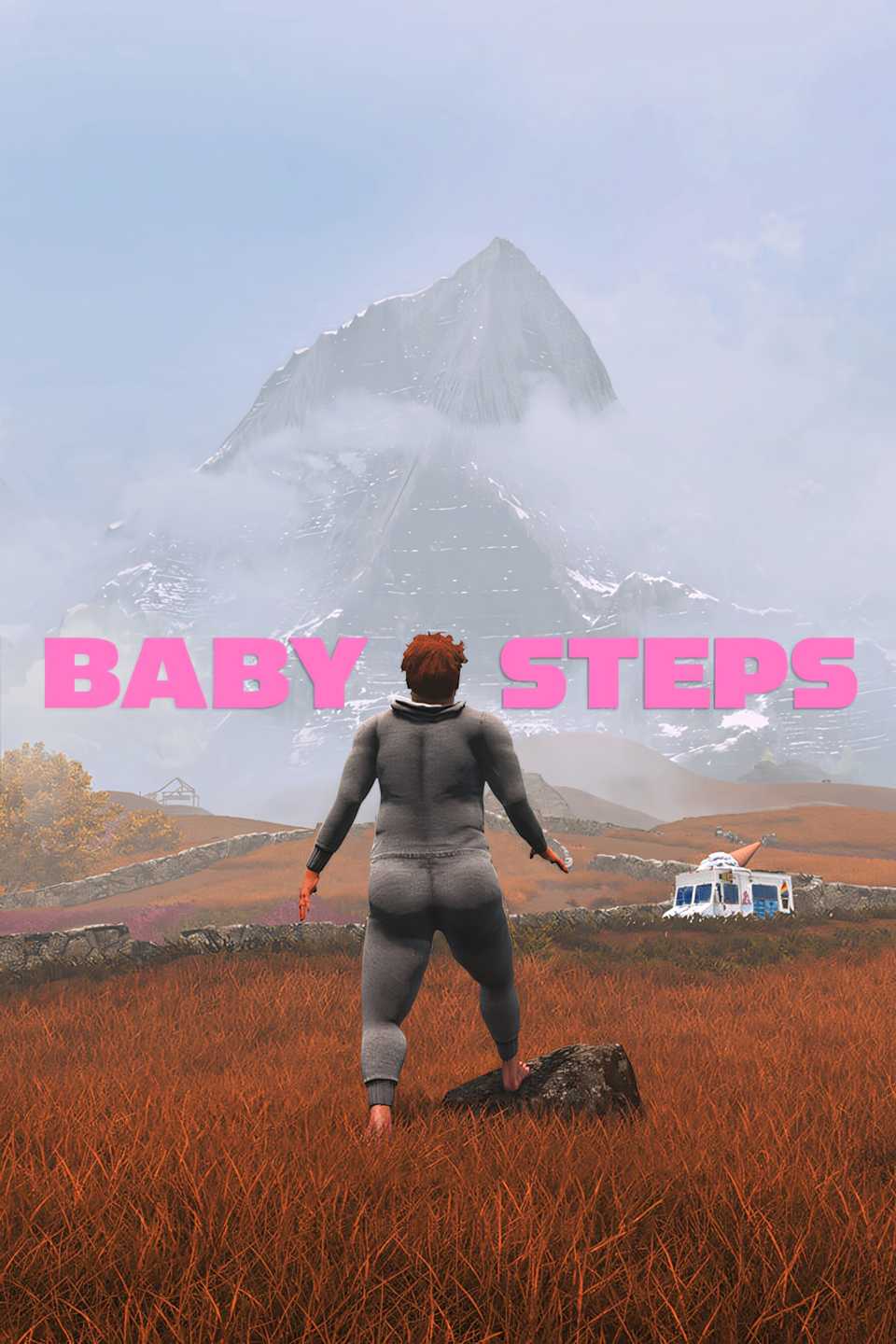

Baby Steps is a walking simulator in the most literal sense of the word. The bizarre concept sees players take control of Nate, an unemployed slacker in his 30s, who is transported from his parents' basement to a mysterious mountainous landscape. There, he must walk, one step at a time, as he traverses a wide range of terrain.

The Best War Games caught up with Baby Steps developers Maxi Boch, Gabe Cuzzillo, and Bennett Foddy to discuss the concept behind the game's interesting premise, and they quickly explained how complex it was to map out the required movement mechanics. This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Baby Steps Focuses Heavily on its Movement Mechanics

The Best War Games: How did you settle on the concept of making the player manually control each footstep rather than traditional movement?

Cuzzillo: This was basically where the game started! At first, your feet would automatically lift as you pressed the stick forward, but pretty quickly it became clear that manually controlling the lifts gave you more control and felt better.

The Best War Games: With walking being such a specifically dedicated mechanic, how did you find a good balance and feel when designing it?

Cuzzillo: It took many years of tuning. The walking system has evolved a lot over the five years of development, and there have been hundreds of minor breakthroughs in making it feel good, consistent and controllable. There are two big underlying themes to balancing and tuning that have been continually re-emerging as we’ve worked on it. The first is what’s the player’s job, and what’s Nate’s job? For instance, how much should he be leaning his torso to try to stay balanced, or how much should he rotate his foot to make getting your foot onto something easier?

The second is how much supernatural balancing force there should be in the system. In general, I don’t like it in physics games when there are “magic forces” making the character move in unjustified ways. A lot of physics games have your controls basically throwing the character around the world with magic forces while the animation tries to catch up. That said, if we had no forces in the game that weren’t justified physically, it would be basically impossible to keep Nate up. Finding the right balance of these two things has been one of the biggest challenges of the development for me, but I’m pretty happy with where it ended up.

The Best War Games: What’s been the biggest technical challenge in building a game so reliant on player-controlled movement dynamics?

Cuzzillo: Figuring out the walking has been by far the biggest technical challenge for me. I really wanted the controls to feel very tight and direct. When you were on stable ground moving your lifted foot, I wanted it to feel more like a shmup than a traditional physics game. Making that work while also keeping the physics stable, and making him animate and move in a semi-natural way, took many years of iteration.

Nate Walking Through Snow

The Best War Games: Can you talk about difficulty and how it applies to Baby Steps, and if that difficulty is adjustable?

Foddy: There are no adjustable difficulty levels in Baby Steps. Our approach is a little different - we make the required stuff pretty easy (by our standards, anyway), but then the more optional or hidden stuff can be harder, way up to stuff that’s extremely spicy. A lot of the beauty in the system is revealed in the hardest parts of it.

Boch: For us, difficulty isn't about trying to harm the player; it's about setting up situations where the player can feel an organic sense of accomplishment, free of systemic inflation, which has become the standard progression path for this sort of action game.

The Best War Games: Stories from play sessions mention finding a “missing cup” and exploring by accident. How important is this freedom to gameplay? What does that mean for individual playthroughs?

Cuzzillo: We wanted to have a fairly loose grip on the player’s experience in this game. We were inspired by a lot of very open-ended games, like My Summer Car and Snowrunner, or even Noita. A big part of what I enjoy about those games is the feeling that you’re exploring a vast space in a very self-directed way. I like feeling like there’s a lot I’m missing, like my experience is only a small subset of what’s in the game. This game plays a lot with both designed and undesigned pieces on many levels.

If you’re just beelining to the end of the game as fast as you can, you’ll probably mostly be engaging with the more intentionally designed parts of the game. There’s a huge range of challenges in the game that go from very carefully designed climbs where every step is considered, to semi-random jumbles of rocks that we discovered were interesting to climb, to things that were built purely for aesthetics that you nonetheless can find ways to walk up. I think we’re doing a similar thing in the cutscenes, which also contain a range of “designed” and “found” humor.

Foddy: Early on, we noticed our playtesters would want to leave the path to investigate something interesting-looking, but were fearful that they wouldn’t be able to get back, so they would enter a kind of FOMO state that we felt was really interesting. We tried to bring that out as much as possible.

Baby Steps Will Have Plenty of Secrets and Hidden Routes For Players to Find

The Best War Games: Trailers have shown Nate interacting with objects, such as knocking a porta-potty off a cliff. Do you have any favorite objects in the world, or any you're particularly excited for players to encounter?

Foddy: This is a tricky one to answer without spoilers, but the announcement trailer shows off a certain skateboard that is pretty fun to interact with.

The Best War Games: How did you approach level design given the more free-form gameplay?

Foddy: It was a pillar for us that if the player falls off a cliff and loses progress, they should end up somewhere that gives them an option of not repeating the same climb they just fell down from. That sense of mercy basically forms the backbone of all the geometry in the game.

The Best War Games: With how non-linear the game looks to be, how do you incentivize players to take more challenging routes? How do you make more daunting paths appealing?

Foddy: Some of the optional routes have a bit of comedy at the end of them. Some of them have a view, just like optional routes in real life. Some of them are only to be climbed for the pleasure of climbing them. I guess we have a belief that there are enough sickos out there that there will be interest in doing the hardest stuff, some of which was not even intentionally designed.

The Best War Games: Can you give any hints towards secrets or hidden areas/routes found in the game that players might wish to seek out?

Cuzzillo: There are so many, it’s hard to choose one to highlight! I think the advice I would give new players is to try not to see everything in the game, enjoy finding what you find and enjoy wondering about what you don’t.

The Best War Games: The world of Baby Steps is more vast and non-linear than that of projects like Getting Over It. How did you balance designing for a more open world with the tightness of level design needed for a game that focuses on a unique set of physics/controls?

Foddy: Designing for an open world with no vehicles, time skips or fast travel is quite a different challenge than designing a traditional open-world game. Cul-de-sacs are a lot more punishing if you have to backtrack out of them, and so are cliffs where you could fall back to somewhere you’ve already been. But it’s also unusual to have to design outdoor spaces where it matters if there’s an individual branch or if a rock is tilted just so. We found that it was overly exhausting if the hiking was technically challenging everywhere you went, though, so it’s not as though we had to sweat the location of every single rock.

[END]

- Released

- September 23, 2025

- Developer(s)

- Gabe Cuzzillo, Maxi Boch, Bennett Foddy

- Publisher(s)

- Devolver Digital

- Number of Players

- Single-player

- Steam Deck Compatibility

- Unknown